The Monastery

Downtown Seattle, 1977

Return to Washington

In 1977, George Freeman relocated to Seattle, Washington, bringing his extensive experience as a nightclub owner and party promoter home to the Pacific Northwest, ultimately creating The Monastery. When he arrived, he found a very different nightlife scene from the one he had become familiar with in New York City. Seattle didn’t have nearly the same fervor for late-night clubs, especially those that opened after 10:00 pm. Seattle’s history as a city in love with strong drink, made bars, not dance clubs, the popular nightlife locales. While New Yorkers preferred private clubs, often without liquor service, Seattleites wanted more democratic spaces with drinks and dancing.

Dating back to the end of Prohibition, Washington State’s legal drinking age has always been 21 – compared to many East Coast states like New York where the drinking age in the 1970s was 18. In Seattle, the over-16 but under-21 crowd had no social venues except cafes, which closed at night.

With no interest in opening a bar, George shifted his aspirations to establishing a New York style private club in Seattle. Traveling around the city, George found himself in front of a run-down church on Boren Avenue in downtown Seattle. It had a “For Rent” sign in front of it, so George jumped at the opportunity.

The Monastery is Born

George quickly worked to transform the space into The Monastery, an after-hours private club which harkened back to his nights as a drummer at Spokane’s Harlem Club and Virgil’s Chicken Dinner Inn. George asked some of his DJs and other associates from Galaxy 21 to relocate. Together, they brought New York-style clubbing to Seattle.

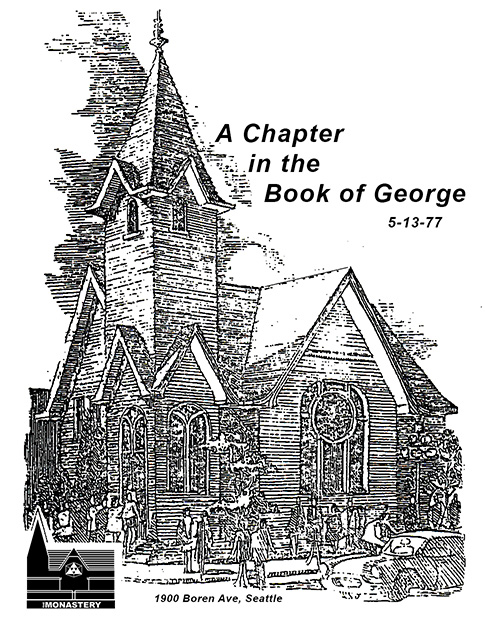

On Friday the 13th of May 1977, a helicopter landed across the street from the Monastery carrying disc jockey John Celick dressed in monk's clothing. He and George then ceremoniously crossed the street and entered the building. With a line stretching around the block and four searchlights illuminating the steeple, so begins the history of The Monastery.

From its earliest days, The Monastery welcomed people from all walks of life. Though it developed a reputation as a gay after-hours club by the late 1970s, the club’s crowd was always a balanced mix of Seattle culture. Its late-night festivities were famous for going straight through to the early morning hours, when George would often provide a free breakfast for all the remaining partiers.

A Place to Be Yourself

The Monastery became a trusted refuge for people who had no place to live, and who had few options for assistance in the socially-conservative Seattle of that decade. Today, Seattle leads the American LGBT rights movement, but the fight for equality was only in its infancy when George’s club first became a major nightlife destination. According to reports from that era, as many as 40% of all homeless youth in Seattle identified as LGBT, while more than a quarter of the city’s homeless youth claimed to be forced onto the streets by their families because of their sexual orientation. Many of them had been thrown out of their churches and ex-communicated, beaten ruthlessly by family members before being asked to leave home. George also had a large number of straight El Salvadoran refugees who knocked on his door seeking assistance, many whom thought the church building was a traditional church.

The Monastery, Before and After 1977 Remodel

Midnight at The Monastery

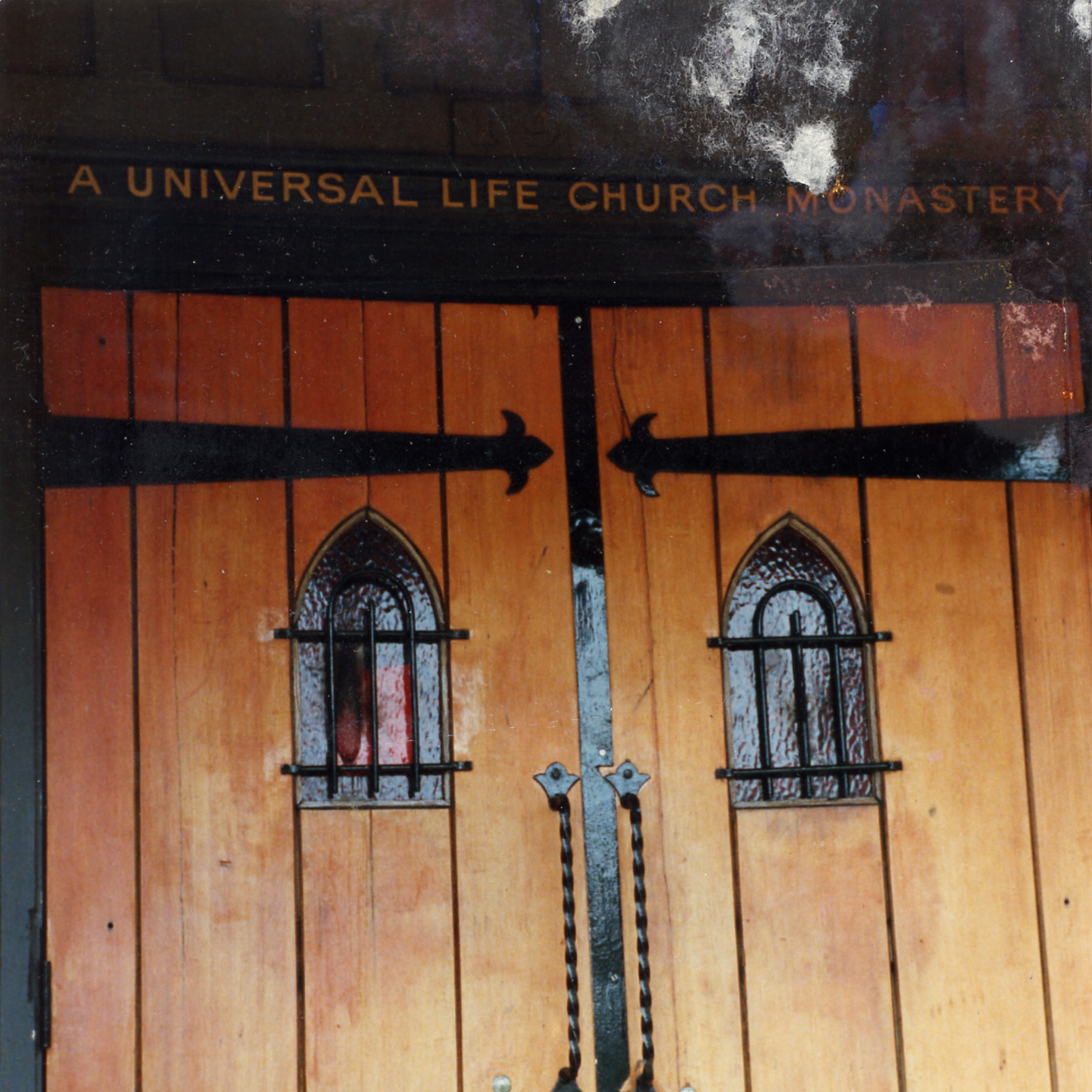

Thus, in addition to being a dance-club, The Monastery also acted as a shelter. By opening its doors to all kinds of people and providing them with a place to sleep, as well as hot food and clothing, the church played a vital role in the community. To facilitate this aid program, the private club became affiliated with the Universal Life Church in order to document the legal use of funds for assisting the homeless. While there was plenty of late-night partying going on, George also instituted efforts to help those he sheltered find their place in the world – the people staying at the club were required to leave during the day and look for jobs.

Despite these good intentions, The Monastery was embroiled in constant controversy. It garnered a reputation as a place where outcast teenagers were exposed to sex and drugs; the age of consent at the time was 16 years of age. While many of these claims proved unfounded, such reports brought substantial negative attention to The Monastery. Formal complaints were filed asserting that Freeman was poisoning the minds of young people, who upon one visit to the club were subject to moral-brainwash. George once stated that emancipation was, according to the Hebrew text, at the age of Bar/Bat Mitzvah, and according to the Christian text, when Jesus was teaching between the age of 12 and 16 according to ancient tradition. The sensitivities of such statements fried the ears of a sleepy Seattle.

Parents-In-Arms

Eventually, city officials decided to act. Attorney David Crosby of Renton, Washington started the activist group Parents-In-Arms to push for new laws in Seattle limiting all-ages gatherings and events. Crosby’s son, Ian, was one of the teens who fled from his home, taking refuge at The Monastery, Skoochies, and other locations. It was his increasing disobedience which sparked Crosby to team up with Seattle prosecutor Norm Maleng and Bill Dwyer, then-president of the King County Bar Association, to take down The Monastery. Incidentally, Ian Crosby today is a highly regarded attorney working in Seattle.

Together, they crafted a plan to use civil procedure to close The Monastery, now an chartered affiliate of the Universal Life Church, on the grounds of it being a moral nuisance. They instructed five undercover police officers to visit The Monastery numerous times over a span of a few months. Their job was to search out drug-dealing patrons and purchase drugs such as cocaine, pot, and MDMA, which they succeeded in doing. After all the allegations, however, the attorneys could not find any evidence to charge the church or any of its employees with drug distribution, sexual misconduct, or even providing alcohol to minors. Turning to plan B, Parents-In-Arms instructed Norm Maleng to use the recently enacted moral conduct civil statues to attack the Monastery. Parents-In-Arms was mainly a Christian fundamentalist group.

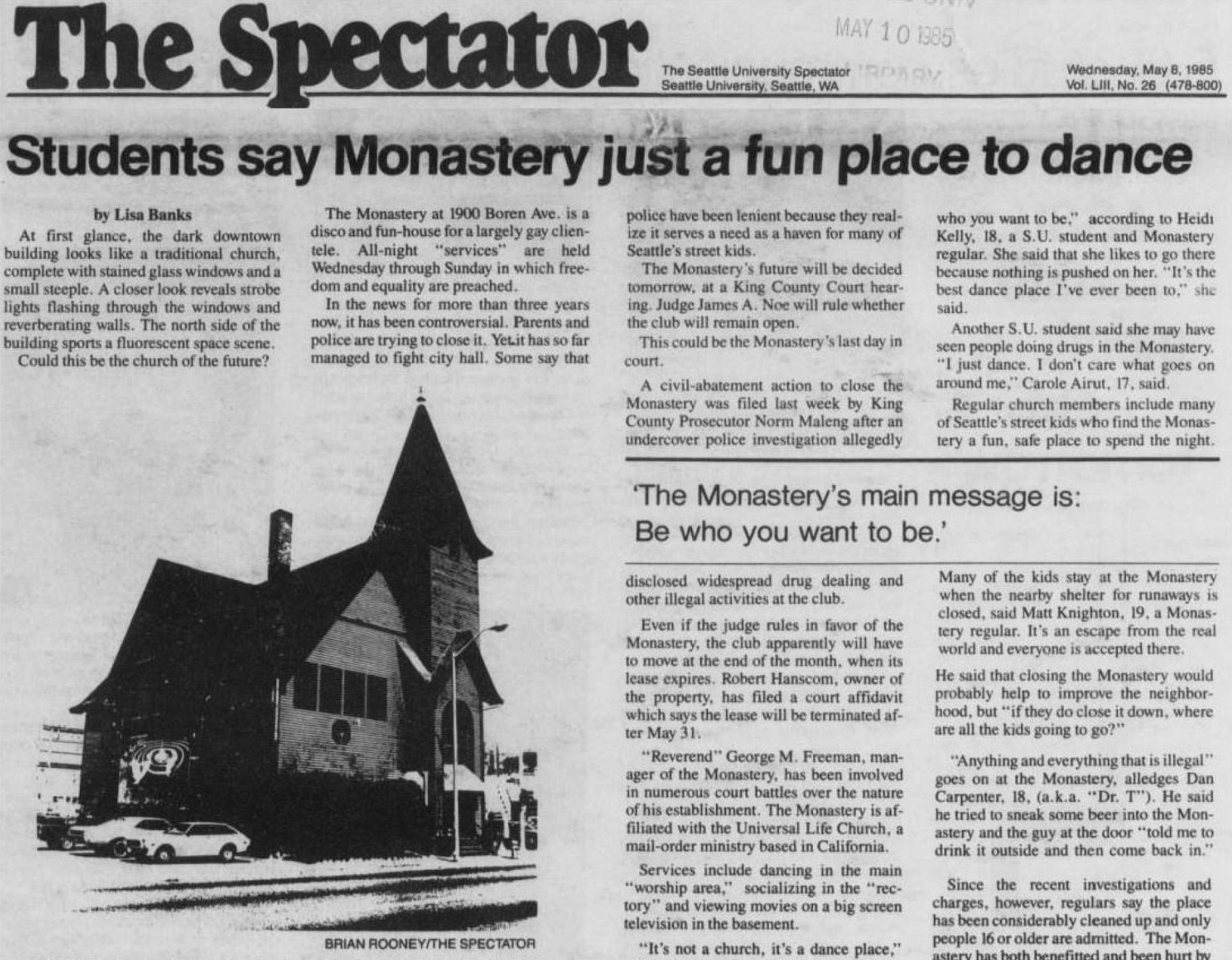

The Spectator, May 1985

Seattle Times, January 1999

End of an Era

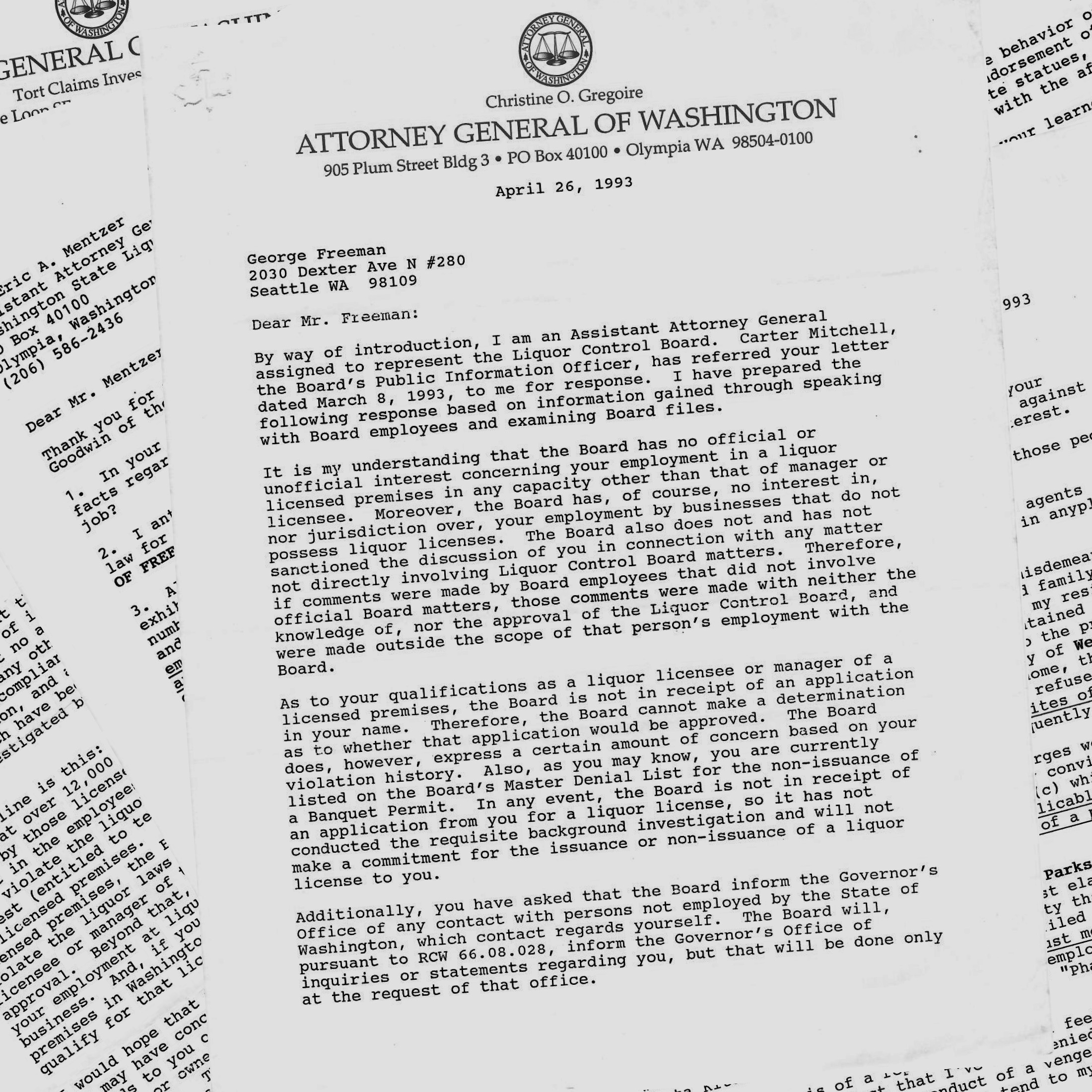

Prosecutors filed civil misdemeanor charges against George for failure to have a $5 banquet permit (which he applied for numerous times but was continuously denied by the State). He was found guilty, and was sentenced to 4 consecutive months in the King County jail. George appealed the ruling, and went to California to build a nightclub while his case was in appeals. Norm Maleng and republican governor John Spellman countered by successfully invoking a Governor’s Warrant, originally intended to help recapture runaway black slaves. In order to bring Freeman back to Washington, Maleng and Spellman quietly enlisted the aid of their fellow republican, governor George Deukmejian of California, to sign a governor’s warrant.

Thus, they were able to override the California courts and obtain a federal extradition order to bring Freeman back to Washington. Freeman subsequently lost his case in appeals, and served his 4-month misdemeanor sentence in the King County jail. The Monastery itself suffered a similar fate – after a long, drawn-out effort to close down the iconic landmark, city officials eventually succeeded in 1985 with an indefinite civil injunction. George has tried numerous times to challenge the injunction, alleging it was illegal, capricious, arbitrary, and fraudulent, through the courts have refused to hear his plea.

Teen Dance Ordinance

One far-reaching consequence of this Republican-backed campaign was the institution of Seattle’s Teen Dance Ordinance. The TDO placed strenuous financial obligations on all-ages dance events, including a stipulation which required supervision by two off-duty police officers and at least $1 million in liability insurance. This functionally made teen dance events in Seattle impossible for almost twenty years. As an unintended side effect of the reactionary policy, the TDO also shut down all-ages concerts and other non-dance events. The TDO was finally repealed in 2002, and was subsequently replaced with the All-Ages Dance Ordinance, which contained more reasonable requirements and paved the way for all-ages events to return to Seattle.

After The Monastery’s eight-year run came to a prejudicial and troubling end, George turned his attentions to the organization that helped him bring aid to so many people in his community, as the founding President of The Universal Life Church Monastery.

Stewart and Boren

"Pilot Your Own Ship" Mural on The Monastery

The Monastery in Spring

Related Articles

The Monastery

Return to Washington

In 1977, George Freeman relocated to Seattle, Washington, bringing his extensive experience as a nightclub owner and party promoter home to the Pacific Northwest, ultimately creating The Monastery. When he arrived, he found a very different nightlife scene from the one he had become familiar with in New York City. Seattle didn’t have the same hunger for late-night clubs, especially those opening after 10:00 pm. Seattle’s history as a city in love with strong drinks, made bars, not dance clubs, the popular nightlife locales. While New Yorkers preferred private clubs, often without liquor service, Seattleites wanted more democratic spaces with drinks and dancing.

Downtown Seattle, 1977

Dating back to the end of Prohibition, Washington State’s legal drinking age has always been 21 – compared to many East Coast states like New York, where the drinking age in the 1970s was 18. In Seattle, the over-16 but under-21 crowd had no social venues except cafes, which closed at night.

With no interest in opening a bar, George shifted his aspirations to establishing a New York-style private club in Seattle. Traveling around the city, George found himself in front of a run-down church on Boren Avenue in downtown Seattle. It had a “For Rent” sign in front of it, so George jumped at the opportunity.

Boren Avenue Church, January 1977

The Monastery is Born

George quickly worked to transform the space into The Monastery, an after-hours private club that harkened back to his nights as a drummer at Spokane’s Harlem Club and Virgil’s Chicken Dinner Inn. George asked some of his DJs and associates from Galaxy 21 to relocate. Together, they brought New York-style clubbing to Seattle.

The Monastery, May 1977

On Friday the 13th of May 1977, a helicopter landed across the street from the Monastery carrying disc jockey John Celick dressed in monk’s clothing. He and George then ceremoniously crossed the street and entered the building. With a line stretching around the block and four searchlights illuminating the steeple, the history of The Monastery begins.

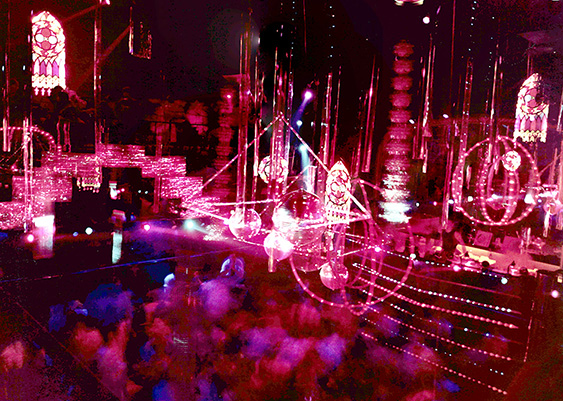

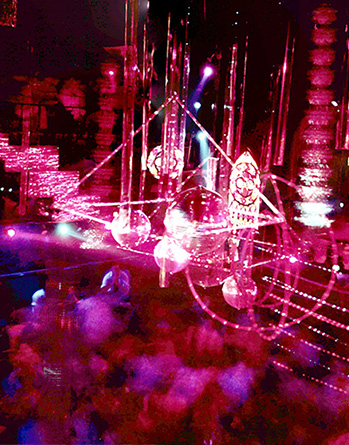

Midnight at The Monastery

A Place to Be Yourself

From its earliest days, The Monastery welcomed people from all walks of life. Though it developed a reputation as a gay after-hours club by the late 1970s, the club’s crowd was always a balanced mix of Seattle culture. Its late-night festivities were famous for going straight through to the early morning hours when George often provided a free breakfast for all the remaining partiers.

The Monastery became a trusted refuge for people who had no place to live and had few options for assistance in the socially-conservative Seattle of that decade. Today, Seattle leads the American LGBT rights movement, but the fight for equality was only in its infancy when George’s club became a major nightlife destination. According to reports from that era, as many as 40% of all homeless youth in Seattle identified as LGBT, while more than a quarter of the city’s homeless youth claimed to be forced onto the streets by their families because of their sexual orientation. Many had been thrown out of their churches and ex-communicated, beaten ruthlessly by family members before being asked to leave home. George also had many straight El Salvadoran refugees who knocked on his door seeking assistance, many of whom thought the church building was a traditional church.

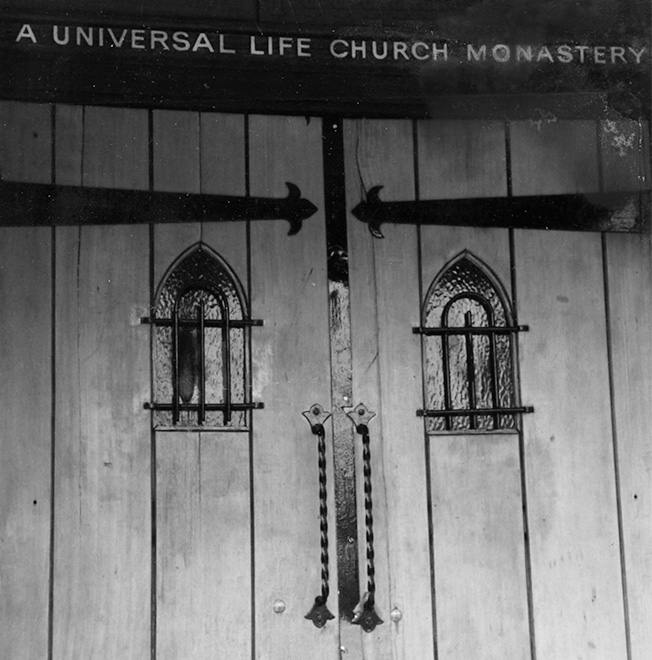

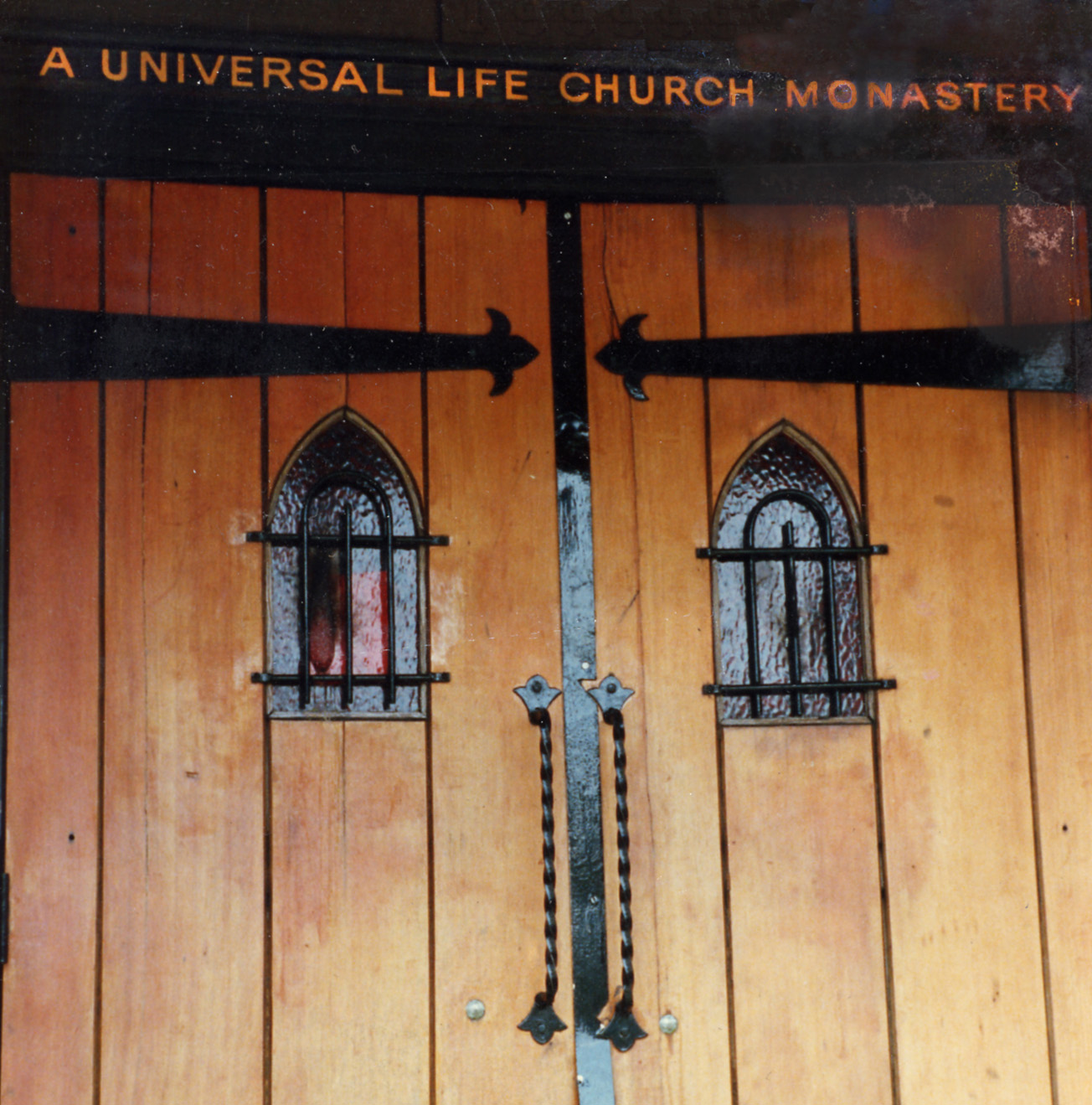

The Monastery Front Doors

Thus, in addition to being a dance club, The Monastery also acted as a shelter. The church played a vital role in the community by opening its doors to all kinds of people and providing them with a place to sleep, as well as hot food and clothing. To facilitate this aid program, the private club became affiliated with the Universal Life Church to document the legal use of funds for assisting the homeless. While plenty of late-night partying was going on, George also instituted efforts to help those he sheltered find their place in the world – the people staying at the club were required to leave during the day and look for jobs.

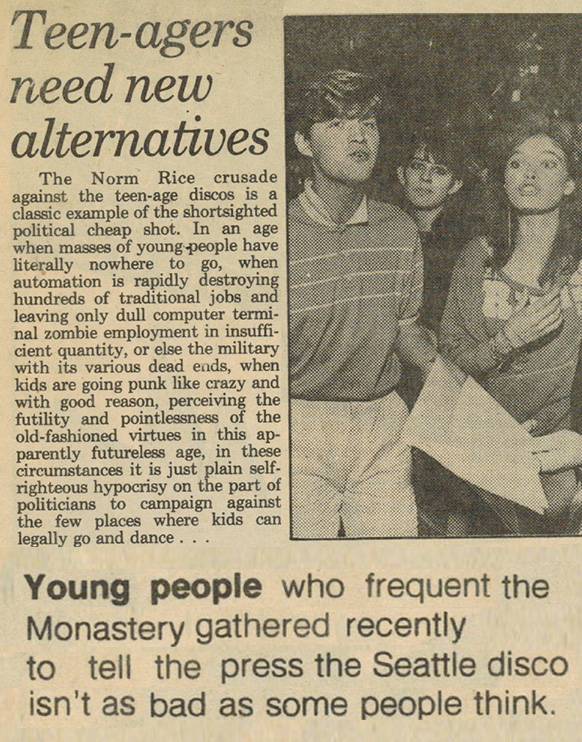

Despite these good intentions, The Monastery was embroiled in constant controversy. It garnered a reputation as a place where outcast teenagers were exposed to sex and drugs; the age of consent at the time was 16 years of age. While many of these claims proved unfounded, such reports brought substantial negative attention to The Monastery. Formal complaints were filed asserting that Freeman was poisoning the minds of young people, who, upon one visit to the club, were subject to moral brainwashing. George once stated that emancipation was, according to the Hebrew text, at the age of Bar/Bat Mitzvah, and according to the Christian text, when Jesus was teaching between the age of 12 and 16 according to ancient tradition. The sensitivities of such statements fried the ears of a sleepy Seattle.

Parents-In-Arms

Eventually, city officials decided to act. Attorney David Crosby of Renton, Washington, started the activist group Parents-In-Arms to push for new laws in Seattle limiting all-ages gatherings and events. Crosby’s son, Ian, was one of the teens who fled from his home, taking refuge at The Monastery, Skoochies, and other locations. Ian’s increasing disobedience sparked his father, Crosby, to team up with Seattle prosecutor Norm Maleng and Bill Dwyer, then-president of the King County Bar Association, to take down The Monastery. Incidentally, Ian Crosby today is a highly regarded attorney working in Seattle.

Together, they crafted a plan to use civil procedure to close The Monastery, now a chartered affiliate of the Universal Life Church, on the grounds of it being a moral nuisance. They instructed five undercover police officers to visit The Monastery numerous times over a span of a few months. Their job was to search out drug-dealing patrons and purchase drugs such as cocaine, pot, and MDMA, which they succeeded in doing. After all the allegations, however, the attorneys could not find any evidence to charge the church or any of its employees with drug distribution, sexual misconduct, or even providing alcohol to minors. Turning to plan B, Parents-In-Arms instructed Norm Maleng to use the recently enacted moral conduct civil statutes to attack the Monastery. Parents-In-Arms was mainly a Christian fundamentalist group.

Seattle PI, May 1985

End of an Era

Prosecutors filed civil misdemeanor charges against George for failure to have a $5 banquet permit (which he applied for numerous times but was continuously denied by the State). He was found guilty and sentenced to 4 consecutive months in the King County jail. George appealed the ruling and went to California to build a nightclub while his case was in appeals. Norm Maleng and Republican governor John Spellman countered by successfully invoking a Governor’s Warrant, originally intended to help recapture runaway black slaves. To bring Freeman back to Washington, Maleng and Spellman quietly enlisted the aid of their fellow Republican, Governor George Deukmejian of California, to sign a governor’s warrant.

Thus, they overrode the California courts and obtained a federal extradition order to bring Freeman back to Washington. Freeman subsequently lost his case in appeals and served his 4-month misdemeanor sentence in the King County jail. The Monastery itself suffered a similar fate – after a long, drawn-out effort to close down the iconic landmark, city officials eventually succeeded in 1985 with an indefinite civil injunction. George has tried numerous times to challenge the injunction, alleging it was illegal, capricious, arbitrary, and fraudulent, through the courts have refused to hear his plea.

Seattle Times, January 1999

Teen Dance Ordinance

One far-reaching consequence of this Republican-backed campaign was the institution of Seattle’s Teen Dance Ordinance. The TDO placed strenuous financial obligations on all-ages dance events, including a stipulation which required supervision by two off-duty police officers and at least $1 million in liability insurance. This functionally made teen dance events in Seattle impossible for almost twenty years. As an unintended side effect of the reactionary policy, the TDO also shut down all-ages concerts and other non-dance events. The TDO was finally repealed in 2002 and replaced with the All-Ages Dance Ordinance, which contained more reasonable requirements and paved the way for all-ages events to return to Seattle.

After The Monastery’s eight-year run came to a prejudicial and troubling end, George turned his attention to the organization that helped him aid so many people in his community, as the founding President of The Universal Life Church Monastery.

The Monastery on Opening Night

Mural On the Side of The Monastery

Downstairs Ministers Quarters, and Musician Green Room

Related Articles

Home | Mind Science |History |Blog | Media | ULC Case Law |Politics |Contact